Three Late Poems and Draft of Merrill's Last Poem

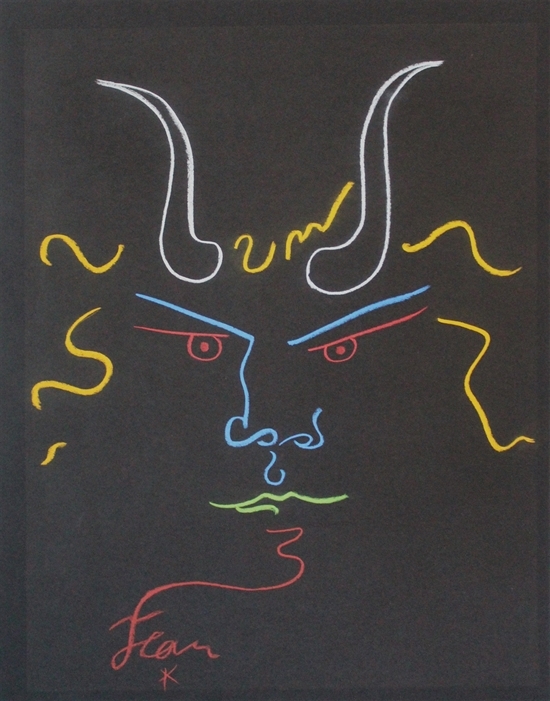

Jean Cocteau's Head of the Minotaur (1961). Pastel. From LiveAuctioneers.com.

THREE POEMS SITE

This site provides teachers and students of James Merrill with an introduction and background to three late poems, "Minotaur" (2001), "Farewell Performance" (1987), and "Investiture at Cecconi's" (1987). The links to this site appear in the left margin. All material is copyrighted. For questions, contact Timothy Materer.

COMMENTARY ON "THREE LATE POEMS": "THE MINOTAUR"

For James Merrill the tale of the Minotaur is the kind of personal myth that W. B. Yeats imagined when he wrote: “I have often had the fancy that there is some one myth for every man, which, if we but knew it, would make us understand all he did and thought (“At Stratford-on-Avon,” Essays and Introductions). Merrill’s nephew, the poet Robin Magowan, also invokes this myth in his memoir about finding his identity within the Merrill family, Memoirs of a Minotaur (1999). Magowan tells of being trapped in a labyrinth of wealth and privilege and in danger of becoming a devouring Minotaur like his father. Magowan’s theme resembles Merrill’s in his novel about his family, The Seraglio, which ends with the adults at a Christening party consuming the candy babies on the cake.

In the Greek myth, a Cretan monster, with the head of a bull and the body of a man, devours seven Athenian young men every year, until the Athenian King, Aegus, sends his son Theseus to challenge the monster. With the help of the Cretan princess Ariadne, Theseus braves the monster's labyrinth and kills the Minotaur. When he returns to Athens, he fails to change the sails from black to white to indicate his survival, and as a result his father throws himself to his death in the sea. Although the labyrinth receives only one mention in Merrill's poem ("through the maze /we’ve come"), it is implied in the word "Amazement" that begins the last stanza; and "Amazement' was JM's working title for the poem until late in the process of composition. Imagery of the maze, often associated (as in Cocteau) with mirrors, pervades Merrill's poetry. In Mirabell the spirit speaks of mankind's "CONCERN WITH TIME THE BEATING OF MAN'S NEW BRAIN / TO ESCAPE THAT MAZE (Sandover 146).

In the halting ten-line stanzas of "Minotaur," Merrill inverts the myth of the sacrifice of the young as he imagines the young Minotaur devouring the lives of ten old men and women, who seem apparently willing sacrifices. Langdon Hammer in James Merrill: Life and Art suggests that the poem was prompted by Merrill's friendship with Torren Blair, who was fifteen years old when Merrill met him in Stonington in 1994. Blair's role in Merrill's life was entirely positive as he tried to absorb Merrill's advice about books, music and life experiences that he should not miss. In terms of the young learning from the old, the Minotaur's hunger for the "Mind's meat heart's blood" is natural and "must have been benign." Blair thought that Merrill "was confronting his own mortality and investing in youth, in someone who was at the beginning rather than the end" (Hammer 788). In addition to his communications with Torren, Merrill was sharing "letters full of life wisdom to several youthful correspondents" (781). And with another friend, Jerl Surratt, whom he frequently saw in New York in the 1990s, he shared the same in their conversations. Surratt recorded a lunch he had with Merrill on September 26, 1994, when the poet gave him a copy of "Minotaur" inscribed with an encouraging message (see Ms. 13).

Merrill wrote in his journal for 24 ix 94: “Poem about teenage minotaur—It’s the 3rd in 5 months. They just come, as they did long, long ago." The manuscripts of "Minotaur" show that the poem developed from its first conception to completion in only three days, September 22-24. Particularly striking is that a complete draft came to Merrill, as noted in Manuscript 9, on "Sept 22 middle of night." (See the Manuscripts link in the left margin.) It sketches in the Minotaur myth and poses the question of the malice or affection of the beast. The manuscript's last lines do not persist into the final version and make sense as a reference to Torren Blair.

He <still> lives in a world before the stoa

The give & take of master & pupil.

A few more years & he will ask [the poet]

. . . .

If he was thinking of Donne when hewrote that line —

The teenage Minotaur is eager to know what the poet knows but not yet mature enough for the kind of critical discourse associated with the Greek classical stoa. The question about John Donne could have been prompted by Merrill's list of essential poems for Torren to read, including Donne's "Valediction: Forbidding Mourning" and "The Ecstasie,” which he listed in his 1995 journal.

Although Torren was apparently in Merrill’s mind when the poem came to him, the more dominant figures behind the poem are Merrill's father, his first lover Kimon Friar, and the lover of his final years, Peter Hooten. Merrill's relationship with his father is explored in the "The Broken Home" website, and his love affair with Friar in "The Black Swan" site. (See the links in the left margin.) In "Minotaur," the threatening father figure appears in the "terrible head" of the Minotaur's father. When the head is laid aside like a mask, the Minotaur looks like a creature in a Jean Cocteau sketch. Imagery of erotic attraction appears in the "portico / pinker than nougat," the alluring "fusion / of grape and cardamom," a limb "firm as cactus / escaping from his cloak," and the fatally attractive "Shafts of blue."

Merrill wrote in his Journal (24 ix 94): “Poem about teenage minotaur . . . . It brings up the whole situation with my mother and Kimon. Who forgets the past is condemned to repeat it. But from a different corner of the triangle." This fear of repeating the past may refer to the recurring patterns in his relationships with Friar and then Hooten. Volumes such as The Black Swan, First Poems, and his novel The (Diblos) Notebook reflect on Merrill's first love affair with his Amherst College teacher Kimon Friar. When Friar, fifteen years older than Merrill, became the lover of his nineteen-year-old student, Merrill's mother intervened, threatened to expose Friar, and sent her son to an analyst to be "cured." But the affair cooled down without or despite Hellen Merrill's interference. Merrill was overpowered by a stronger personality from whom Merrill was soon alienated. Hammer writes that Merrill

must have recognized that, while Friar promised to free him from his parents’ control, he would have to free himself from Friar’s, too. When Friar published The Black Swan, Merrill had completed his private course of study [as Friar's student]. But it would take a long time before he asserted his intellectual independence from Friar to his own satisfaction. It was much easier to give up Kimon as a lover. “Kimon is back but, oh, with a difference,” Jimmy wrote in his diary on January 4, 1947. He was afraid of turning cold, of forgetting how to feel, but he was also afraid of Friar and wanted “calm”: it had cost too much to fight with his mother. So he told Friar he “couldn’t cope” with their relationship any longer. The rupture left him “numb, confused, guilty”(pp. 99-100).

Kimon was the lover in Merrill's first affair, and Peter Hooten was in Merrill's final relationship. Written in Merrill's late sixties, "Minotaur" is a reflection of both affairs; he is now the troubled lover of Peter Hooten, who is almost twenty-five years younger. Like Friar, Hooten fed on the generosity and glamor of Merrill's personality. Hammer writes that one of Merrill's old friends took offense at Hooten's "'increasingly close imitation of Jimmy's dress, speech, gestures, manners, and opinions,' as if he were appropriating, not merely sharing, the life of her friend (p. 689). Hooten drew heavily on Merrill's financial resources when, with Hooten's career as a movie actor over, they collaborated on Voices from Sandover, a stage version of The Changing Light at Sandover that they also filmed. Hammer explains that both the stage and video version of the work were failures, despite the enormous production costs (perhaps as much as $800,000).

Peter was the film’s producer. He had devoted more than a year to it, had been swept up in “the euphoria” of making it, and was “terribly” depressed at its reception . . . these days he was increasingly given to “tantrums,” those “Old Testament” rages that Merrill had come to fear. Fueling Hooten’s anger were “binges” on alcohol, pot, or cocaine (pp. 752-753).

Yet even in these difficult times Merrill could consider Peter the "answer to a prayer" (Hammer 691); and as Merrill suffered increasingly from AIDS-related illnesses, Peter seem "more wonderful every week," and cared for him during his last months. He told a friend in an unsent letter of 1994 that Peter had "saved my life": "From my point of view I've never had that kind of caring from anyone" (785). The last lines of the poem show that any understanding of the relationship of the young Minotaur to its victims or devotees depends on one's point of view. The poem's narrator concludes of the experience:

It must have been benign

if we lived through it Did we

Depends who tells the tale.

How willing was the "sacrifice"? Was the experience creative or destructive for the old ones? At the bottom of Manuscript 5, Merrill wrote "Feelings 'returned' - feelings rejected? The vital thing is to have the experience." The Minotaur may transmit death, but it also offers the erotic passion needed for life. One may question or regret the consequences in hindsight, but not the original experience.

"FAREWELL PERFORMANCE"

The mythic reach of "Minotaur" extends past Merrill's relationships with any one figure in his life and helps us understand the conflicted feelings expressed in “Farewell Performance” and “Investiture at Cecconi’s,” which are both dedicated to David Kalstone and commemorate his death from AIDS. (As "The Farewell Performance" link at left shows, an actual farewell performance was danced by the New York City Ballet in Balanchine’s Mozartiana [1981], which Suzanne Farrell dedicated to Kalstone.) These poems explore the connection of love with death as does "Minotaur." The dancers in "Farewell Performance" possess the same deadly attraction as the young Minotaur. The poet's friend has “caught like a cold their airy / lust for essence" from the "sweat-soldered" dancers. Hammer uses the drafts of the poem to illuminate the striking phrase about lust and essence, and also explains the coded nature of what might seem an abstract term, "essence":

In his drafts, Merrill had “taken on” instead of “caught” and “rage” instead of “lust”— easier words. But he wanted to bring up the sexually transmitted infection that led to DK’s death. Merrill is suggesting that art not only fails to save us; it may not be good for us. And “essence” adds a further twist. In personal columns and pornography, the word was a code advertising black men and women through an allusion to Essence, the magazine for African Americans that began publishing in the 1970s (p. 713).

Despite the dangers, the dancer's fans "jostle forward," with phallic “programs furled, lips parted . . . eager to hail them" (CP 582). In Manuscript 20, Merrill describes not only the dancers' "sacrificial rage for essence" but also "the dark rites" "whereby flesh / Yields its essence." The dancers appear "Gasping, & drenched . . . [they] beg forgiveness," but cannot look directly at their devotees: "staring eyes But the dancers / will not meet them." In Manuscript 25 the dancers appear: "Dripping, subdued, they stand there . . . gasping for pardon."

The grand opening statement of the poem, "Art. It cures affliction" also disintegrates in the course of the poem. In the finished poem, the "pure, brief" gold of the dancers' art becomes the crematorium's "mortal gravel" (581). (At the bottom of Manuscript 13, Merrill writes, "life is not art.")

The drafts of the poem allow us to glimpse how the poet worked through the bitterness of his emotions to compose a statement that allows for some consolation. Almost every draft describes the comforting ritual of the poet and his partner rowing out from Stonington to release Kalstone's ashes into the Connecticut sound. The slow, falling rhythm of the poem's Sapphic verse form, and its sorrowful but reserved tone, moderate the bitter and far more critical judgments of the dancers in the poem's drafts. The finished poem ends with the resigned judgment that if one looks closely at the dancers

their magic

self-destructs. Pale, dripping, with downcast eyes they've

seen where it led you. (CP 582)

"INVESTITURE AT CECCONI'S"

Although "Investiture at Cecconi's" is a less bitter poem than "Farewell," the joy the speaker feels when he learns of his friend's gift of a kimono is also deeply qualified. The speaker makes a dream-like visit (based on Merrill's actual dream) to the Venetian tailor Cecconi (see the link to "David Kalstone's Milieu" in the left margin) and learns that Kalstone has left a gift for him even though he is still at home mortally ill. Rachel Hadas notes that gift of the kimono is "double-edged" and that the white kimono is a metaphor for AIDS. Even so, Hadas emphasizes the "passionate connection" the kimono represents and suggests that the living do not die "if they are artists, without having passed on their gifts to still others, in an endless reticulation of connections, a fertile cloud of cross-fertilization" (Merrill, Cavafy, Poems, and Dreams, 44).

This view of the artist and aesthetic experience is undercut, however, by the irony that the passionate connections extend the reach of the fates that may sever one's life. The poem's last line states that the gift of the kimono is a "heartstopping" present. In Manuscript 8, which is not yet in Sapphic stanzas, the last line is "You had arranged this final gift for me." ("Final" is, to use Hammer's expression, an easier word.) But below in the left margin Merrill has typed in "heart-stopping gift," and then written in the phrase "heart-stopping present."

Since Merrill knew he was seriously ill when he wrote "Investiture," the diagnosis referred to in the poem's first line is not Kalstone's alone. Merrill's journal notes his diagnosis with ARC (AIDS Related Complex) at the Mayo Clinic in April 1986. The circumstance of Merrill's death from a heart attack when in a condition weakened by AIDS underlines the poem's crowning irony that the "heartstopping present" (CP 580) is deadly. Merrill is not of course hinting that his love specifically for Kalstone was fatal. Although Alison Lurie records, in her memoir Familiar Spirits, Merrill's quip that he might have contracted AIDS "from David Kalstone's razor" (173), she notes that the statement is obviously implausible. Instead, it emphasizes as does "Farewell Performance," the obvious and tragic fact that the disease can be transmitted by intimate contact among friends and lovers.

In addition to Hadas, other critics differ from my reading of the poems in their greater emphasis on Merrill's assertions of the solace of art and community. For other perspectives (with footnotes), and a more extended analysis of the poems, see the link to the "Survey of Literary Criticism" in the left margin.