"The Black Swan," Kimon Friar, and Merrill Interview

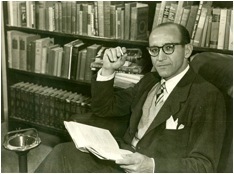

"The Black Swan" may be read as a love poem for Merrill’s teacher Kimon Friar (1911-93) as well as a meditation on a poetic image. According to Friar, Merrill referred to him as the "black swan" because his complexion turned so dark in the summer. Friar recalls this in an interview in "The Man Who Couldn't Remember: Conversations with Kimon Friar" (Southeastern College, 1990). Friar is now best known as the translator into English of modern Greek poets such as George Seferis, Constantine Cavafy, and Nikos Kazantzakis. In 1945 he taught at the Poetry Center in New York and was teaching at Amherst College as a temporary instructor in the veteran’s program. In James Merrill: Life and Art (NY: Knopf, 2015), Langdon Hammer notes that Friar lectured on "The Swan in Literature and Painting" at the Poetry Center in New York (92-93).

Friar was fifteen years older and living the literary life that Merrill wished for himself. He accepted Merrill as his informal poetry student, and one of the assignments he gave was to write a poem about a swan and a lake in a certain meter and stanza. Merrill turned the exercise into a poem for the man he describes in his memoir, A Different Person, as his "first love” (Collected Prose 473)).

The outcome of the affair is described in Merrill's memoir. In December 1945 Merrill's mother opened a letter from Merrill to Friar revealing the intimacy of the relationship. During a meeting she arranged in New York, the two men were forbidden to meet or even speak with one other; but they both were allowed to return to Amherst to finish out the academic year. After escaping this potential scandal at Amherst, Friar left for Greece in June 1946 while Merrill (still only twenty and without the independent income he would enjoy at twenty-one) spent a summer under the watchful eyes of his mother and grandmother.

Publication of The Black Swan (1946)

Not only "The Black Swan," but also many of Merrill's early poems, concern the crisis over Friar. The Black Swan was conceived by Friar himself as a collection of poems concerning their love affair. Friar suggested publishing the volume when he asked Merrill in August 1946 to send him a poem he had misplaced. He suggested printing a volume that would collect these love poems in one place in a permanent form. Although Friar claimed that he paid for the publication, Merrill sent Friar the money for publication expenses October 1946. In addition to "The Black Swan," the poems that seem most likely to concern this affair include "The Formal Lovers," "Suspense of Love," "Medusa," and "Embarkation Sonnets" (concerning Friar's departure for Greece). The Black Swan is dedicated to Friar with an epigram in Greek drawn from Euripides' Iphigenia in Aulis, which Merrill translated in the copy he inscribed for Friar: "Of all my friends I have found you most a friend" (Special Collections, Washington University). The dedicatory ten-line poem of the volume, which begins "Keats on board ship for what we shall call Rome" (Collected Poems 677), refers to Friar, whose students flattered him by comparing him to Keats, departing for Athens. The initial letters of the poem's ten lines spell out KIMON FRIAR.

Friar’s “In Childhood’s Chair”

"The Black Swan" is thus a declaration, in "anguish," that Merrill loves the black swan in spite of the "white ideas" of the conventional world. (The rewritten poem in Merrill's 1984 volume From The First Nine changes “anguish” to “Now in bliss, now in doubt" and reflects a more mature understanding of his life.) Friar challenged Merrill to acknowledge his homosexuality publicly. But defiance was possible only in Merrill's mind, and Friar soon realized that Merrill was not yet independent enough to defy his family. Friar reflects on this situation in a poetic reply to "The Black Swan" that he published in Poetry in 1957 (90.4), "In Childhood's Chair." A matriarch sits in "childhood's chair," regarding the children with a Medusan gaze. Merrill appears as the "blond child running . . . . To a white seashore and a sunlit sea," and Kimon as a "black" child who is the figure of the poet in the form of Perseus. (Merrill referred to Friar as "Perseus" in the journal he kept at Amherst.) He holds a "flaming sword," mastering the Medusa, and making "monstrous love" with the blond child. The poem seems to reflect the meeting Friar and Merrill had with Mrs. Merrill in New York when Merrill defiantly insisted that he would always love Kimon.

For further information on Merrill and Friar, see Langdon Hammer’s Masks of the Poet (American College of Greece, 2003) and his biography James Merrill: Life and Art (Knopf 2015).

The Interview

Merrill on "The Black Swan" from the Paris Review Interview (Summer 1982) with J. D. McClatchy.( Link to the complete review.) In "The Man Who Couldn't Remember," Friar remarked on Merrill's statement that the Black Swan poems had "simply bubbled up": "By 'bubbled up'; I take it he doesn't mean that most of the poems he had written in that period were not problems I had set for him, but that they were written--as I've noted previously--so quickly, in a day or so, in preparation for the following lesson" (80).

INTERVIEWER

How would you now characterize the author of "The Black Swan" ?

MERRILL

This will contradict my last answer about “starting out in the fifties.” By then I’d come to see what hard work it was, writing a poem. But The Black Swan—those poems written in 1945 and 1946 had simply bubbled up. Each took an afternoon, a day or two at most. Their author had been recently dazzled by all kinds of things whose existence he’d never suspected, poets he’d never read before, like Stevens or Crane; techniques and forms that could be recovered or reinvented from the past without their having to sound old-fashioned, thanks to any number of stylish “modern” touches like slant rhyme or surrealist imagery or some tentative approach to the conversational (“Love, keep your eye peeled”). There were effects in Stevens, in the Notes, which I read before anything else—his great ease in combining abstract words with gaudy visual or sound effects . . . “That alien, point-blank, green and actual Guatemala,” or those “angular anonymids” in their blue-and-yellow stream. You didn’t have to be exclusively decorative or in deadly earnest. You could be grand and playful. The astringent abstract word was always there to bring your little impressionist picture to its senses.

INTERVIEWER

But he—that is, the author of "The Black Swan"—is someone you now see as a kind of happy emulation of literary models?

MERRILL

No, not a bit. It seems to me, reading those poems over—and I’ve begun to rework a number of them—that the only limitation imposed upon them was my own youth and limited skill; whereas looking back on the poems in The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace, it seems to me that each of at least the shorter ones bites off much less than those early lyrics did. They seem the product of a more competent, but in a way smaller, spirit. Returning to those early poems now, obviously in the light of the completed trilogy, I’ve had to marvel a bit at the resemblances. It’s as though after a long lapse or, as you put it, displacement of faith, I’d finally, with the trilogy, reentered the church of those original themes. The colors, the elements, the magical emblems: they were the first subjects I’d found again at last.